Steering Clear of Sexually Secure Women

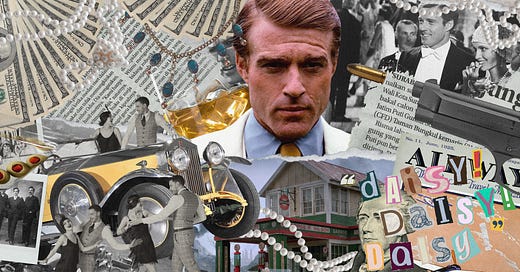

An analysis of masculine anxiety and the threat of female autonomy in The Great Gatsby.

“It’s when Daisy gets behind the wheel of Gatsby’s yellow roadster… that she indisputably achieves femme fatale status.”

- Maureen Corrigan

Like most novels, The Great Gatsby is a product of its time. Centered in the elitist circle of the 1920s, evidence of this time’s outdated views on race, immigration, and gender are exceedingly prevalent, dominating the actions of the characters and driving the plot forward.

The latter of these is especially prominent, though, materializing in the time’s slow shift in gender roles and the expansion of that for women. With this new sense of female autonomy, the threat of what this could mean for men and their position in the patriarchy takes shape in the form of masculine anxiety, struggling to maintain their control.

In the novel, this can be demonstrated through the character’s acts, like Daisy and Myrtle’s attempts at gaining this power, as well as Tom’s efforts at extinguishing them. Unfortunately, this all comes to rear its ugly head by the novel’s conclusion, following Myrtle’s tragic death, Daisy’s position as the one behind the wheel, and Tom’s ill-advised decision to redirect the blame.

The Fin-de-Siècle Crisis in Masculinity

To better comprehend the severity of these claims, understanding the period of which this novel stems from and what this means for masculinity and femininity is essential. In “F. Scott Fitzgerald, Modernist Studies, and the Fin-de-Siècle Crisis in Masculinity,” Greg Forter describes the modernization of these terms that arose immediately before the completion of Fitzgerald’s novel and the effect that it had on its themes.

This period—1890 to 1920—was a time in which “masculinity was in crisis” in response to “a breakdown in gendered roles” that followed the increasing prevalence of monopoly capitalism and “reduced men to dependents in a large bureaucratic structure” (Forter 296-297).

Before, “manhood” would be defined by a man’s ability to “achieve economic autonomy, self-sufficiency, and ownership of productive property” while simultaneously embodying a “range of softer virtues” to balance this more aggressive assertiveness—“moral compassion, self-restraint, emotional sensitivity” (Forter 296-297). Not only did this rise disrupt a man’s ability to achieve such a status, but this sense of dependency was soon compared to femininity and emasculating traits, causing men to drop the latter half of this previous definition of manhood and fall deeper into that hostile side of the coin.

This is where the sense of masculine anxiety stems from—in trying to overcompensate with aggressive assertiveness so that one does not appear too feminine—and with The Great Gatsby achieving publication in 1925, this concept is extremely prevalent throughout.

Icons of The Roaring Twenties

With this, there is also the beginning of the shift in a woman’s role in society. Daisy Buchanan, as a character, defies the expected gender norms of the period—she is promiscuous and freely drinks, fully embodying the personal freedoms that arose with the “flapper” image. She exudes an air of confidence in her sexuality, as well as a sense of certainty in the effect this has on men:

“‘If you want to kiss me any time during the evening, Nick, just let me know and I’ll be glad to arrange it for you’” (Fitzgerald 80).

Daisy knows that she is attractive, almost arrogantly assuming everyone sees this as well, and she welcomes this attraction, even verbally encouraging it despite the vows she made to Tom. This completely disbands the previous role of women in pleasant society, who should act as the pure, innocent accessory for their husbands to flaunt on their arm, tucked away by their side and in their shadow.

There are moments where Daisy embodies this caricature—“‘Are you in love with me,’” she once asked, feigning ignorance as if she was unaware of her influence on others—but where it matters most, she breaks these proverbial rules (Fitzgerald 66).

In the end, Daisy is portrayed as a selfish elitist who lacks any sort of a conscious; she is shallow, hurtful, and cruel, especially in her treatment of others. To her, everyone else is expendable, with the rare exception of those who can fulfill her materialistic desires, and she has no regard for other’s feelings—and, more importantly, other’s lives.

While this leads to further discussion on Daisy’s neglect for the time’s cookie-cutter image that she is expected to squeeze into, this complete disrespect for others ties into the way in which society views her in this period’s newfound autonomy in women.

Manifestations of Masculine Anxiety

This easily connects to the concept of masculine anxiety that runs rampant in Fitzgerald’s work, especially through Tom’s character. Tom is the perfect manifestation of masculine anxiety, and this is best expressed through his interactions with Daisy and Myrtle, who have learned how to weaponize their femininity to push the agenda of their own autonomy.

Daisy does so in a patronizing manner—“‘Tom’s getting very profound,’ said Daisy, with an expression of unthoughtful sadness. ‘He reads deep books with long words in them’”—which is used to undermine the high position in society that Tom believes he inhabits as a wealthy white man (Fitzgerald 13). In this, Daisy understands Tom’s incessant desire to portray himself in such a manner that aligns himself with these previous views on manhood, and she makes this statement to undermine these attempts, showcasing how he is not any better than her because he reads these books.

Myrtle is a bit more obvious in her independence, especially when Tom says that she is not allowed to talk about Daisy:

“‘Daisy! Daisy! Daisy!’ shouted Mrs. Wilson. ‘I’ll say it when I want to!’” (Fitzgerald 30).

Tom feels threated by this show of feminine power, and his violent reaction solidifies just how far he is willing to go to secure his masculinity—an attack on his manhood cannot go unpunished.

Both these women represent not only this period’s shift in gender roles and the sense of independence that women have slowly begun to gain, but also the ways in which men react to it and the lengths they are willing to go to defend their position in the patriarchy.

The Horrors of a Woman in Control

The car crash from the third act further pushes this idea of a women’s role in the early twentieth century. Maureen Corrigan best demonstrates this in So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came To Be and Why It Endures, analyzing the scene of Myrtle’s death from this perspective with an emphasis on Daisy’s role as the getaway driver.

In this, she expresses how “to be behind the wheel is to be in control, and for a woman to occupy that place is… upsetting to the conventional hierarchies” (Corrigan 145). In placing Daisy in the driver’s seat, not only does this drive the plot forward in a domino-effect of tragedies, but it also demonstrates Fitzgerald’s own fears regarding female agency and the power that women could hold had they not been sequestered in society.

There is also an emphasis on the victim to this crime, Myrtle, who is another character that follows unconventional gender roles in the form of sexual liberty—her affair with Tom—and worldly desires. She escapes from the prison of her home and runs out to the car, assuming that Tom was driving it because he had been earlier; however, it is Daisy behind the wheel, who ends up taking her life.

With this, there is the notion that a woman in control is damaging to other women, though this particular instance adds another layer in that men are damaged too—as a direct result to this crime, Gatsby is killed by George, who then turns the gun on himself.

“It’s when Daisy gets behind the wheel of Gatsby’s yellow roadster… that she indisputably achieves femme fatale status” (Corrigan 145).

This backs Fitzgerald’s negative views of women holding any sense of authority and how detrimental this feminine power can be by linking Daisy’s autonomy to the tragedy of three lives lost.

Final Thoughts…

Through this, it is clear that Fitzgerald was writing with the times, allowing his own insecurities in his manhood to assert themselves not only in the characters, but also the plot itself.

At the conclusion of the novel, it is evident where he stands on such topics, as well as the hopes and fears he has for his fellow gender, and this is especially prominent in Tom’s actions preceding the car accident. Without him redirecting the blame of Myrtle’s death to Gatsby, Daisy would have instead faced persecution—whether that come in the form of a trial or George’s own twisted sense of justice—and she was unable to defend herself.

By taking control of the situation and rewriting the narrative to better aid in his own desires, Tom is again reasserting himself as the powerful, masculine pawn in the patriarchy, first by starting with the splintered gender dynamics governing his own home.

In this, he is reminding Daisy that—despite her attempts at achieving female autonomy—he will always be that much stronger than her and there is absolutely nothing that she can do about it. Tom will always be the one in power, and Daisy will always be “the fool.”

Corrigan, Maureen. So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came To Be and Why It Endures, eBook, Little, Brown and Company, 2014.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. The Great Gatsby. New York, Scribner, 2018.

Forter, Greg. “F. Scott Fitzgerald, Modernist Studies, and the Fin-de-Siècle Crisis in Masculinity.” Duke University Press, vol. 78, no. 2, June 2006, pp. 293-323. doi:10.1215/00029831-2006-004.